The West Pole Archive

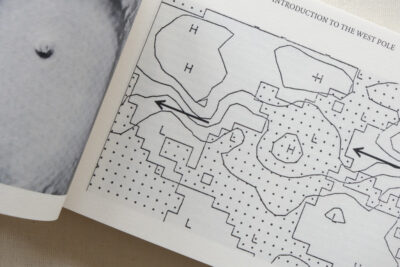

The West Pole is a critical inquiry into the matters of environmental visibility as well as into the possibilities of reclaiming landscape imaginaries and establishing a new type of more-than-human observer. The West Pole observer attempts to find alternative modes of comprehending the world around and dismantle the tired dualisms of the past. The observer who adapts the process of ‘seeing’ or rather ‘sensing’ the landscape to the critical reality of the late anthropocene and climate urgencies that we all dwell in.

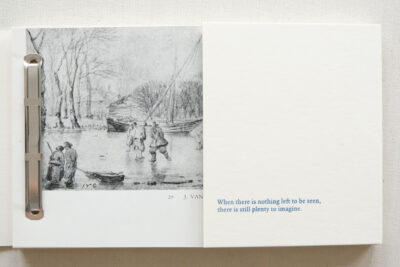

Building the techniques of observation on co-dwelling and kinship with non-human species, the protagonist of the West Pole expedition follows the steps of Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing – developing the strategies of living in the ‘damaged world’. Her kinships are built not only with invisible, microscopic creatures teeming inside the dunes and mud, but also with macro-agents, such as geological and climate formations. All of them become participants of joint landscape cognition. The invisibility of these participants does not diminish their power.

If previously the site of vision was located inside human bodies (or rather in their heads) (Crary, 1992), this new kind of observer participates in a collective or shared process of landscape cognition. Thus, the observation site expands and exceeds the human bodily frame. Landscape and its dwellers co produce the geographical observation with a human being. With the shift to less anthropocentric epistemologies, the geographical sight also shifts from centeredness in the human apparatus to multiple agents. This requires the extended sensitivities that are either shared with non-human participants or picked up from them as signals. Certainly, the interpretation of the signals is still mostly performed through the prism of human cognition. But the geography of cognition here shifts from the intellectual to the bodily one.

The landscape of the West Pole belongs to “more-than-human geographies” in which, as Michel Serres puts it, “there is sense in space before the sense that signifies” (1991, 13). The West Pole becomes the protagonist of the story, taking over the agency from the human actor, who humbly occupies the role of vigilant observer, eager to learn from the landscape and sees herself merely as a “flea in the thick, yellow fur of dunes.”

The West Pole observer pursues the tactics of ‘oscillation’ (Rose 1993) and ‘bewilderment’ (Halberstam 2020). Counter-hegemonic, these modes are built around unlearning the previous ways of seeing/knowing landscape, as well as developing new patterns of attention.

We find the mentioning of oscillation in one of the geographical treaties of Gillian Rose. She writes (1993, 183):

Oscillation for its own sake is not the point, then: the goal of such a critical mobility must be to deconstruct the polarities that it oscillates between. The structure of the Same and the Other must be destabilized.

The diary echoes Rose: “The West Pole is in a state of constant trepidation . . . The antagonisms of wild and cultured, sublime and mundane, visible and invisible are dissolved in this trembling dance.” The oscillation technique resonates with the landscape itself. Thus, the new type of observation does not only exceed the human body, it also synchronizes with the environment around.

Crary, Jonathan. 1992. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halberstam, Jack. 2020. Wild Things : The Disorder of Desire. Durham: Duke University Press.

Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rose, Gillian. 1993. Feminism and Geography.The Limits of Geographical Knowledge. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Serres, M. 1991. Rome: The Book of Foundations. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Tsing, Anna. 2015.The Mushroom at the End of the World.On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.